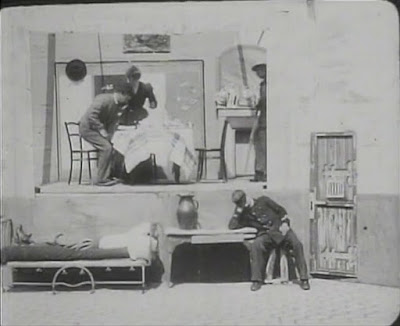

Histoire d'un Crime (1901)

Should the period from early film to early cinema (1895-1927) be considered as a film language in its own right, or was it a primitive search for the narrative form we have now?

Much valuable progress in the art of film storytelling was made in the time of "silent film," from the first films of Lumière to the advent of Warner Bros' "The Jazz Singer" (US, 1927, dir. Alan Crosland). Comparing the single unmoving tableau shot of "Sortie d'Usine" ("Workers Leaving the Lumière Factory", France, 1895) with the complicated special effects, storyline and "cast of thousands" in "Metropolis" (Germany, 1925, dir. Fritz Lang) shows the quantum leap made in thirty years, now a relatively short period in the history of cinema.

However, defining the "cut-off point" in this period history at the advent of sound film does not separate early film and early cinema from what followed, as if silent cinema was a separate art and discipline.

The argument for the silent era being an evolutionary period in filmmaking was taken up by Barry Salt who, in his article "Film Form 1900-1906", he looks at the first instances where certain film devices were used - this is because he notices that the development of style in early film has "some analogies with biological evolution, in the way that novel features which suddenly appear like mutations are sometimes rapidly taken up in other films, forming a line of descent, while on other occasions original devices die out because they have some unsuitability of a technical, commercial or artistic nature." (Salt 1990: 31)

Salt notices that, while a dream sequence in "Histoire d'un crime" (France, 1901) appears within the frame of the existing action, the practices of dissolves between the dream and the main action is fully established by the time "And the Villain Still Pursued Her" (US, 1906) was made. This approach to finding first instances of what would become techniques is continued throughout Salt's essay but, when it comes to trick effects, Salt concludes that the large amount of trick films made to 1906 are over-estimated in their importance to the history of cinema as a whole (Salt 1990: 40).

|

| The Gay Shoe Clerk (1903) |

Meanwhile, in an article entitled "The Cinema of Attractions: Early Film, Its Spectator and the Avant-Garde", Tom Gunning considers early film to about 1906-07 to have its own form, in which the illusory power of the new technology could be explored. Instead of the "voyeuristic" nature of later, narrative cinema, the "cinema of attractions... is an exhibitionist cinema... [it] is a cinema that displays its visibility, willing to rupture a self-enclosed fictional world for a chance to solicit the attention of the spectator." (Gunning 1990: 57)

Early film came before the days of an institutionalised cinema industry, cinema chains, and even before nickelodeons. You were most often to see a film either as a fairground attraction, or as part of a bill at a music hall. Spectacle is dominant over narrative in film at this point.

The two schools of thought may conflict, as developments in film techniques may be seen, from a different perspective, as another way of using film to exhibit something - "The Gay Shoe Clerk” (US, 1903, dir. Edwin S. Porter) is seen as a development in the use of the close-up on a key point in the film's plot - the lifting of a lady's skirt to reveal her ankle while being fitted for new shoes. However, according to Gunning, "...its principal motive is again pure exhibitionism." (Gunning 1990: 58) The act of revealing the ankle is, in this case, included to provide titillation for the viewer.

The word "film" became universally recognised as a one-reel dramatic narrative from around 1907-08, coinciding with the industrialisation of film, experiments in technique did continue around this. For D.W. Griffith, such experimentations "were for him the unformulated results of practical problem-solving rather than abstract theorizing... Unrestricted by narrative conventions, since there were few at the time, Griffith simply adopted for his Biograph films what worked best in the particular circumstances, according to the dynamics of the tale." (Cook 1996: 62)

|

| The Lonedale Operator (1911) |

It is well-documented that Griffith also used theatrical techniques and the dramatic structure of Charles Dickens’s novels in his films. As an example of the former, the beginning of "The Lonedale Operator" (US, 1911) shows characters leaving the frame on one side, but re-entering in the next scene from the same side - just as you would in a theatre. This was suitable for audiences at a time when such theatrical techniques were more greatly recognised. However, when someone enters through a door later in the film, they leave the frame on one side, but enter the next scene on the opposite side. To use the same technique as described above for this particular piece of action may cause confusion, and wouldn't look right on the screen.

The "novel structure" helps to attract the new middle-class audience in picture houses that was beginning to replace the working-class in nickelodeons as the main target film audience, and, therefore, may be seen as the reason why narrative cinema replaced the "cinema of attractions". According to Gunning (1990: 57), exhibitionist cinema either moved underground - e.g. "Un Chien andalou" (France, 1928, Luis Bunuel), which depicted the dreams of the director and Salvador Dali in a series of irrational images and short narratives - or became incorporated into narrative cinema, like the boxing match in "Broken Blossoms" (US, 1919, D.W. Griffith) provides a break in a melodramatic storyline, while the whole genre of "comedian comedies" (Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton, Harold Lloyd, Harry Langdon etc.) features spectacle around a continuing narrative.

It can be argued that the advent of sound brought new ideas to push cinema in a new direction, while silent cinema was effectively ended as an industry within a few years. However, the basis for further growth in this period of cinema was possible due to the developments during the earlier period. There are cases when early film and early cinema can be seen as art in its own right (as trick films and exhibitionist films were mainly concentrated before 1906, for example), but it was instrumental in the search for narrative form.

The notion that early film and early cinema were a primitive search for narrative form seems inappropriate - it suggests that such exploration was confined to the late-19th and early-20th centuries. However, the central questions for any filmmaker - what can the technology do, and what can they do with it - is still relevant today.

|

| Un Chien Andalou (1928) |

Bibliography

Salt, B. (1990) "Film 1900-1906" in Elsaesser, T. (ed.) Early Cinema: Space, Frame, Narrative. London: British Film Institute. pp. 31-44.

Gunning, T. (1990) "The Cinema of Attractions: Early Film, Its Spectator and the Avant-Garde" in Elsaesser, T. (ed.) Early Cinema: Space, Frame, Narrative. London: British Film Institute. pp. 56-62.

Cook, D.A. (1996) A History of Narrative Film (3rd ed.) London: W.W. Norton & Company Ltd.